2. 清华大学 机械工程系, 高端装备界面科学与技术全国重点实验室, 北京 100084;

3. 清华大学 机械工程系, 精密超精密制造装备及控制北京市重点实验室, 北京 100084

2. State Key Laboratory of Tribology in Advanced Equipment, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China;

3. Beijing Key Laboratory of Precision/Ultra-precision Manufacturing Equipment and Control, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

随着中国综合国力的提升与经济社会的发展,建设海洋强国已被纳入国家的重要战略目标[1],而水下装备是进行海洋探索、开发所必需的工具。其中,水下多自由度机器人(如机械臂等)可以安装于舰船、海上平台、水下无人航行器等母体上作为作业工具,在海洋资源勘探、科学考察、工程建设维护等各个领域均有广泛的应用前景[2],具有较高的研究与实用价值。

目前,水下多自由度机器人已有串联、并联、软体等不同种类。串联水下多自由度机器人发展较早,技术相对成熟,已有众多型号实现了量产,如Shilling公司的TITAN水下机械臂、Hydro-lek公司的HLK系列水下机械臂等[2]。学者针对不同的实际应用需求对水下串联作业机械臂及其末端执行器开展了研究。例如,Tang等[3]研究的一种超冗余索驱动串联水下机械臂通过冗余自由度适应复杂多变的作业环境;Bae等[4]为一种自主式水下航行器(autonomous underwater vehicle,AUV)设计了双机械臂系统以提高其抗扰能力,并结合流体力学特性对双机械臂构型进行优化。相比串联水下多自由度机器人,并联水下多自由度机器人的相关研究相对较少,其主要应用场景是实现水下航行器的矢量推进[5-6]。此外,Simoni等[7]为一款作业型AUV设计了类Delta构型串并混联六自由度机器人作为执行机构,并分析了该机器人的正、逆运动学和工作空间。软体水下多自由度机器人方面,Phillips等[8]提出一种海水液压驱动的水下软体机械臂,相比刚性机械臂,功率大幅降低,且更适用于海洋生物的采样。然而,以上3类水下多自由度机器人的工作范围通常均在10 m以内,难以满足远距离、大工作空间水下作业的任务需求。

索驱动并联机器人采用柔性的绳索代替连杆,保留了并联机器人惯性较小、负载能力强的特点,同时也具有广阔的作业空间[9],目前被广泛用于起重搬运[10]、射电天文[11]、康复医疗[12]等领域。近年来,已有学者提出将索驱动并联机器人用于水下场景。例如,Zarebidoki等[13]提出利用此类机器人实现水下航行;El-Ghazaly等[14]提出使用绳索辅助AUV的运动,形成绳索-推进器混合驱动机构,其研究主要关注机器人末端的力施加性能;Horoub等[15]提出一种六索驱动海洋浮动平台,并分析了该平台在波浪力作用下的工作空间;Gouttefarde等[16]设计了一种八索并联水下垃圾清除装置并开展了实地测试。以上各类装置均采用重力或浮力张紧绳索,这使得机构在水平方向的运动能力受到动平台尺寸的限制,同时,这种被动的张紧方式不利于绳索索力的调节。针对被动张紧方式的不足,可以考虑添加辅助支链或螺旋桨等机构,如Zi等[17]和Zhang等[18]均为索驱动并联机器人设计了辅助弹簧支链以保持绳索张紧。Lee等[19]和Seo等[20]对索驱动爬壁机器人的研究中,都采用螺旋桨提供对墙壁的附着力;Hayashi等[21]提出一种具有轻质量动平台的协作索驱动并联机器人,并在动平台上安装螺旋桨以张紧绳索。但采用螺旋桨提供张紧力的方案在水下运动装置中的研究还相对较少,需要进一步探究。此外,已有的装置中绳索驱动器均安装于静平台上,需要预先留出安装位置,难以在已建成的水下设备中使用,且不利于发挥索驱动机构的可重构性。

本文以水下远距离、大空间作业任务为背景,提出一种基于变推进力机构的近端索驱动机器人。该机器人可方便安装于水下运动装置表面,通过6根绳索与螺旋桨共同驱动,螺旋桨推进力及其方向分别通过其自身转速与推进力变向机构调节。对该机器人进行了结构设计,并建立其运动学与静力学模型,进一步提出一种基于约束二次规划的工作空间计算方法,对恒方向和变方向推进力条件下的力可行工作空间进行分析。结果表明,通过引入推进力变向机构显著增大了机器人的工作空间,解决了已有水下多自由度机器人作业空间不足的问题。

1 水下近端索驱动机器人的结构设计水下近端索驱动机器人主体为1个近端六索驱动并联机构,通过螺旋桨提供的推进力实现绳索张紧。推进力大小可由螺旋桨转速调节,同时引入1个两自由度变向机构以改变推进力的方向。

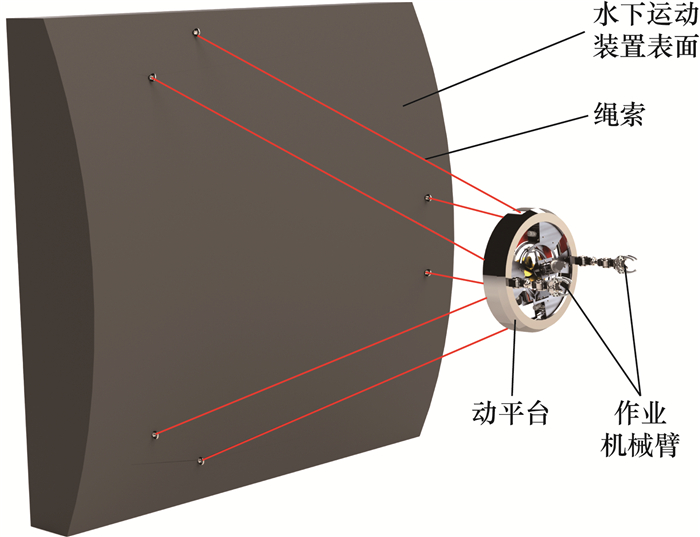

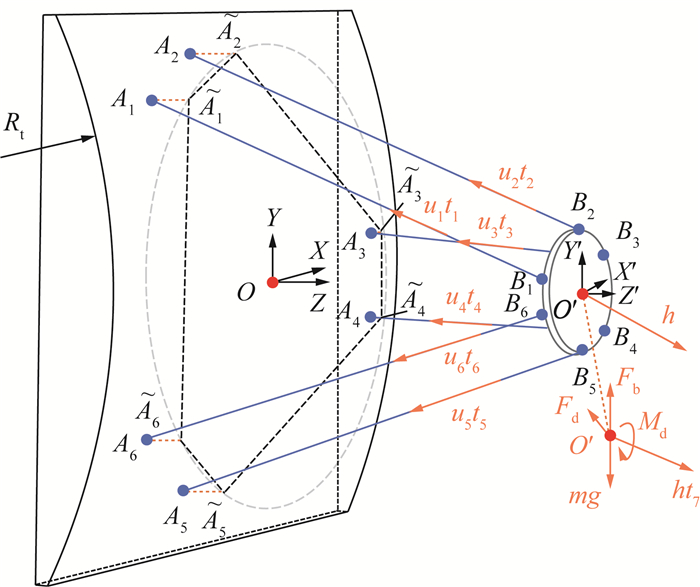

水下近端索驱动机器人的总体结构如图 1所示。其中,近端驱动结构通过将所有绳索驱动单元安装于动平台内的方式来实现。机器人只需完成绳索的悬挂即可开始工作,布局安装较为便捷,且对水下运动装置本体影响较小。机器人的6根绳索一端从动平台的驱动装置引出,另一端连接到水下运动装置表面,呈六边形分布。除绳索外,动平台中同时安装螺旋桨提供推进力,通过推进力(可近似等效为1根绳索)和6根绳索,即可实现动平台的六自由度运动。此外,动平台上可配备1对用于作业的串联机械臂,以完成抓取、搬运等作业任务。

|

| 图 1 水下近端索驱动机器人总体结构 |

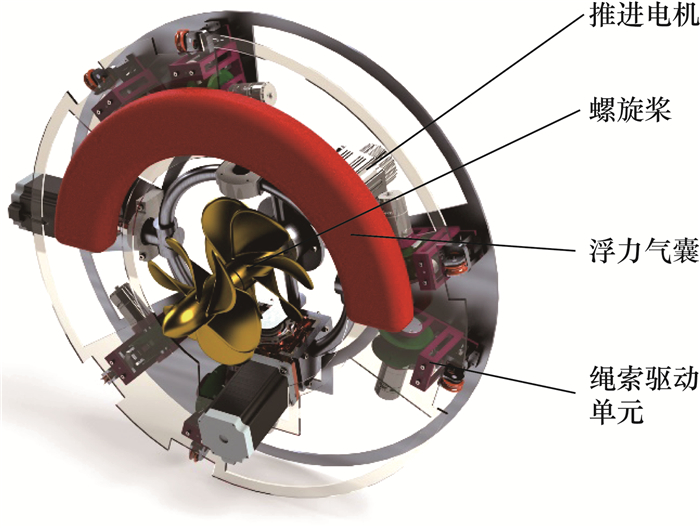

图 2为动平台内部的近端驱动结构。每根绳索均由各自独立的电机驱动,螺旋桨由推进电机驱动。考虑到单个螺旋桨除产生推进力外,也会对动平台产生附加力矩作用,该附加力矩会严重影响末端执行器的控制精度。因此,本研究采用同轴反转螺旋桨机构,即通过2个转动速度相同但转动方向相反的螺旋桨抵消扭矩,如图 3所示。本文中,该方案采用锥齿轮传动实现。

|

| 图 2 水下近端索驱动机器人动平台驱动结构 |

|

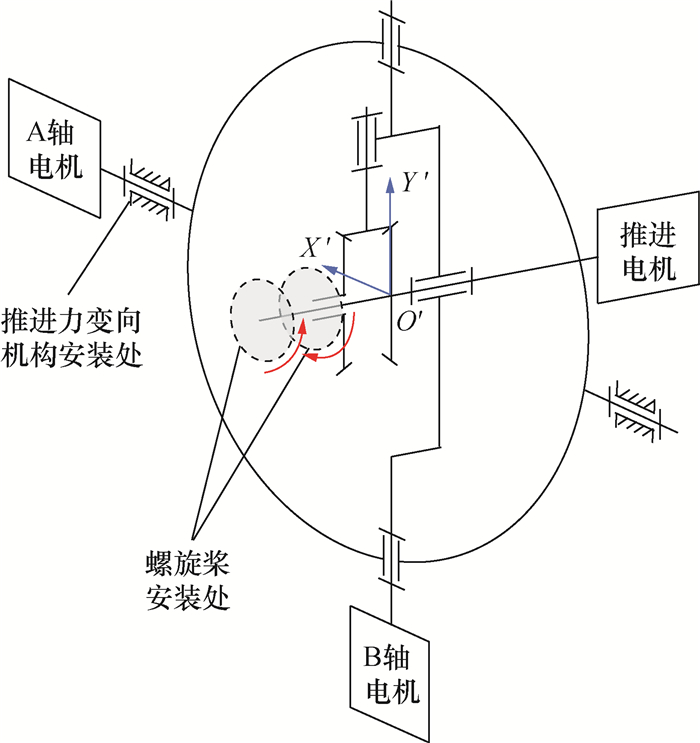

| 图 3 推进力变向机构与同轴反转螺旋桨机构简图 |

为实现推进力在X和Y方向上的变化,提出了一种具有两自由度转动功能的推进力变向机构,原理如图 3所示。该机构安装于机器人动平台中,由A和B两轴串联组成,2根轴的转动可分别由1个电机控制;转动轴采用曲轴设计,从而为螺旋桨的安装提供足够的空间。此外,动平台内安装有气囊,使得动平台的总重力与浮力平衡,通过调节质量分布可实现动平台质心O′与几何中心重合,从而使推进力对O′的力矩为0。

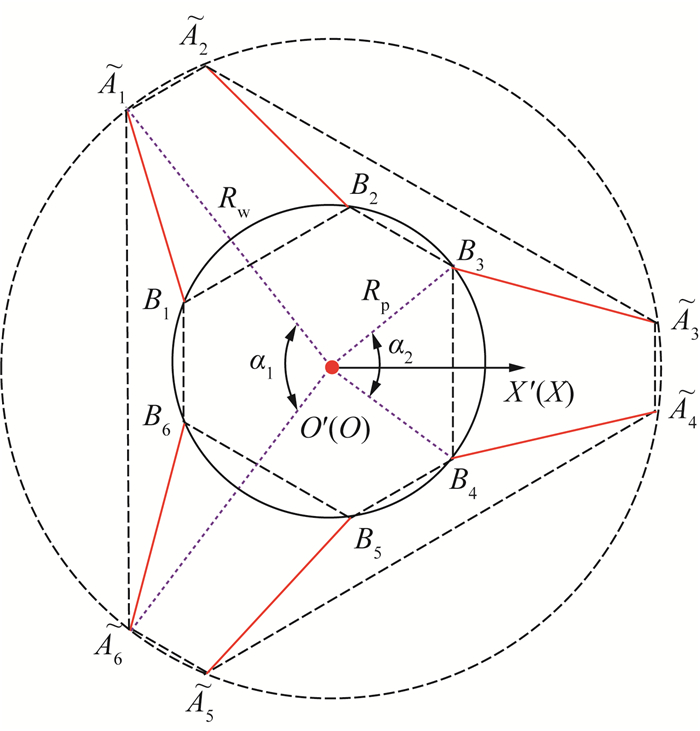

2 运动学与静力学分析 2.1 运动学建模根据第1章所展示的设计结构,建立水下六索并联机器人的运动学模型如图 4所示。将图 1的水下运动装置外形近似建模为圆柱体,设其横截面半径为Rt。在圆柱侧表面上选取一点O建立全局坐标系O-XYZ,其中Z轴正向为点O处侧表面的外法线方向,X轴与圆柱体轴线平行。

|

| 图 4 机器人运动学模型示意图 |

|

| 图 5 初始状态下运动学模型示意图 |

在图 4中,p为O′相对于O的位移矢量,ai为静平台上各绳索连接点相对于O的矢量,ri为动平台上各绳索连接点相对于O′的矢量。由于机器人尺度不足以引起绳索下垂,且在水下环境中工作,因此可忽略绳索自重,并将其建模为直线。设li为各绳索矢量,由动平台指向静平台,根据矢量封闭原理可得运动学关系如下:

| $ \begin{align*} & \boldsymbol{l}_{i}=\boldsymbol{a}_{i}-\boldsymbol{p}-\boldsymbol{R}_{0}{ }^{o^{\prime}} \boldsymbol{r}_{i}, i=1, 2, \cdots, 6 ; \\ \boldsymbol{R}_{0}= & \left(\begin{array}{ccc} \mathrm{c} \psi \mathrm{c} \phi & -\mathrm{s} \psi \mathrm{~s} \theta+\mathrm{c} \psi \mathrm{~s} \phi \mathrm{~s} \theta & \mathrm{~s} \psi \mathrm{~s} \theta+\mathrm{c} \psi \mathrm{~s} \phi \mathrm{c} \theta \\ \mathrm{~s} \psi \mathrm{c} \phi & \mathrm{c} \psi \mathrm{c} \theta+\mathrm{s} \psi \mathrm{~s} \phi \mathrm{~s} \theta & -\mathrm{c} \psi \mathrm{~s} \theta+\mathrm{s} \psi \mathrm{~s} \phi \mathrm{c} \theta \\ -\mathrm{s} \phi & \mathrm{c} \phi \mathrm{~s} \theta & \mathrm{c} \phi \mathrm{c} \theta \end{array}\right). \end{align*} $ | (1) |

其中:R0为O′-X′Y′Z′相对于O-XYZ的旋转矩阵,在本文中采用Z-Y-X Euler角(θ, ϕ, ψ)表示, c和s分别为余弦(cos)和正弦(sin)函数的缩写;O′ri是Bi在O′-X′Y′Z′中的位置矢量。在式(1)基础上,计算绳索长度如下:

| $ l_{i}=\left\|\boldsymbol{l}_{i}\right\|_{2}=\left\|\boldsymbol{a}_{i}-\boldsymbol{p}-\boldsymbol{R}_{0}{ }^{O^{\prime}} \boldsymbol{r}_{i}\right\|_{2} . $ | (2) |

图 6为机器人动平台在水中静止状态下的受力状况。

|

| 图 6 机器人的静力学模型示意图 |

根据受力与力矩平衡关系可以得到机器人的静力学平衡方程:

| $ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{t}+\boldsymbol{h} t_{7}+\boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}=\mathbf{0}, \\ \boldsymbol{A}=\left(\begin{array}{cccc} \boldsymbol{u}_{1} & \boldsymbol{u}_{2} & \cdots & \boldsymbol{u}_{6} \\ \boldsymbol{r}_{1} \times \boldsymbol{u}_{1} & \boldsymbol{r}_{2} \times \boldsymbol{u}_{2} & \cdots & \boldsymbol{r}_{6} \times \boldsymbol{u}_{6} \end{array}\right) \in \mathbb{R}^{6 \times 6}, \\ \boldsymbol{t}=\left(\begin{array}{llll} t_{1} & t_{2} & \cdots & t_{6} \end{array}\right)^{\mathrm{T}} \in \mathbb{R}^{6}, \\ \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}=\binom{\boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{b}}+m \boldsymbol{g}+\boldsymbol{F}_{\mathrm{d}}}{\boldsymbol{M}_{\mathrm{d}}} \in \mathbb{R}^{6} . \end{gathered} $ |

其中:A为索驱动并联机器人的结构矩阵,t为索力向量,ui=li/‖li‖2∈

| $ t_{i} \in\left[t_{\min }, t_{\max }\right], i=1, 2, \cdots, 6. $ |

t7为螺旋桨提供的推进力大小,h=(hX hY hZ hθ hϕ hψ)T,其中前3个元素和后3个元素分别代表单位推进力在动平台各个方向的力和力矩。此外,机器人动平台也受到浮力Fb、重力mg和外界干扰力Fd及其力矩Md的作用,以上几个变量均表示为3维向量。通过调节浮力气囊,可抵消动平台重力,使其处于中性浮力状态,因此在后面的分析中不考虑重力和浮力的影响。

3 工作空间分析 3.1 力可行工作空间的定义力可行工作空间(wrench-feasible workspace, WFW)是指在给定的一组外力螺旋和机器人自身的索力范围限制下,机器人能够保持自身平衡的一组位姿[23]。本文中,机器人可实现六自由度运动,其完整力可行工作空间V⊆

| $ \begin{gather*} \exists t \in\left[\boldsymbol{t}_{\min }, \boldsymbol{t}_{\max }\right], t_{7} \in\left[0, t_{7 \max }\right] , \\ \boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{t}+\boldsymbol{h} t_{7}+\boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}=\mathbf{0} . \end{gather*} $ | (3) |

除需满足前述力可行条件外,在求解机器人的力可行工作空间时,也需要考虑结构矩阵的特性及干涉现象。归一化A可得

| $ \boldsymbol{A}_{1}=\operatorname{diag}\left(1, 1, 1, \frac{1}{R_{\mathrm{p}}}, \frac{1}{R_{\mathrm{p}}}, \frac{1}{R_{\mathrm{p}}}\right) \boldsymbol{A}. $ |

当A1的条件数cond(A1)过大(大于10)时认为机器人的可控性较差,无法满足实际工作要求(A1奇异也包含在这种情况中)。因此,在力可行工作空间内的位姿应满足可控性指标:

| $ \operatorname{cond}\left(\boldsymbol{A}_{1}\right) \leqslant 10 . $ | (4) |

此外,对于干涉现象,主要考虑绳索与水下运动装置的圆弧形表面发生干涉,由于本机器人动平台运动的角度范围较小,绳索构型无交叉,故绳索之间和绳索与动平台之间的干涉均很难发生。绳索与圆柱表面不发生干涉的条件可用绳索单位向量ui与表面外法向量n的内积表示:

| $ \boldsymbol{n}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{u}_{i} \leqslant 0, i=1, 2, \cdots, 6 . $ | (5) |

根据式(3)—(5)即可判断某一位姿是否属于机器人的力可行工作空间。在此基础上固定动平台姿态角,将三维位置空间离散为网格,并对每一格点分别判断以上条件,即可获得以离散形式表达的机器人力可行工作空间。

3.2 基于约束二次规划的工作空间计算方法3.1节提出的力可行工作空间求解方法中,最关键的问题是式(3)所示的力可行条件的判断。对于本文提出的推进力方向可变的索驱动并联机器人,本节中将对变推进力的特点及取值范围进行分析,并对推进力集合的约束进行微小的近似调整,此后,提出一种二次规划方法以有效判断近似力可行条件是否成立。

由图 3可知,推进力方向的2个转动自由度为串联关系,在绕X轴转动的自由度的基础上进行绕Y轴的转动。根据机器人的机械结构设计,可认为推进力作用于动平台质心,且无额外的力矩作用。故以下只考虑h的前3个元素作为变量,将后3个元素设为0,采用推进力向量hXYZ=(h1 h2 h3)T=(t7hX t7hY t7hZ)T代替t7h。当A可逆时,t与hXYZ的关系为

| $ \boldsymbol{t}=-\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}-\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}. $ |

其中(A-1)XYZ为A的逆矩阵的前3列。

设A、B两轴的最大转角均为ξ,本文中ξ为15°左右。A、B轴转角分别用γA、γB表示,则hXYZ在O-XYZ中可表示为

| $ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{h}_{\mathrm{XYZ}}=t_{7} \boldsymbol{R}_{0} \boldsymbol{R}\left(x, \gamma_{\mathrm{A}}\right) \boldsymbol{R}\left(y, \gamma_{\mathrm{B}}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{array}\right)= \\ t_{7} \boldsymbol{R}_{0}\left(\begin{array}{c} -\sin \gamma_{\mathrm{B}} \\ \sin \gamma_{\mathrm{A}} \cos \gamma_{\mathrm{B}} \\ \cos \gamma_{\mathrm{A}} \cos \gamma_{\mathrm{B}} \end{array}\right). \end{gathered} $ |

hXYZ的模长受到t7max的限制,此外hXYZ的方向也受到ξ的约束。同时考虑hXYZ模长、方向的约束与力可行条件,可得到1组关于hXYZ的不等式,作为A可逆时力可行条件成立的充分必要条件:

| $ \left\|\boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}\right\|_{2} \leqslant t_{7 \max } , $ | (6) |

| $ -\tan \xi \sqrt{h_{2^{\prime}}^{2}+h_{3^{\prime}}^{2}} \leqslant h_{1^{\prime}} \leqslant \tan \xi \sqrt{h_{2^{\prime}}^{2}+h_{3^{\prime}}^{2}} , $ | (7) |

| $ -h_{3^{\prime}} \tan \xi \leqslant h_{2^{\prime}} \leqslant h_{3^{\prime}} \tan \xi , $ | (8) |

| $ h_{3^{\prime}} \geqslant 0 , $ | (9) |

| $ \boldsymbol{t}_{\min } \leqslant-\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}-\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z} \leqslant \boldsymbol{t}_{\max } . $ | (10) |

其中hX′Y′Z′为O′-X′Y′Z′中hXYZ的表示,hX′Y′Z′=(h1′ h2′ h3′)T=R0ThXYZ。从形式上看,式(6)—(10)构成的不等式组中,式(6)可视为凸二次约束,式(8)—(10)均为线性约束,仅式(7)为非凸约束。然而考虑到ξ为15°左右,此时对式(7)进行线性近似的误差较小,故将该式近似转化为式(11)的线性约束:

| $ -h_{3^{\prime}} \tan \xi \leqslant h_{1^{\prime}} \leqslant h_{3^{\prime}} \tan \xi . $ | (11) |

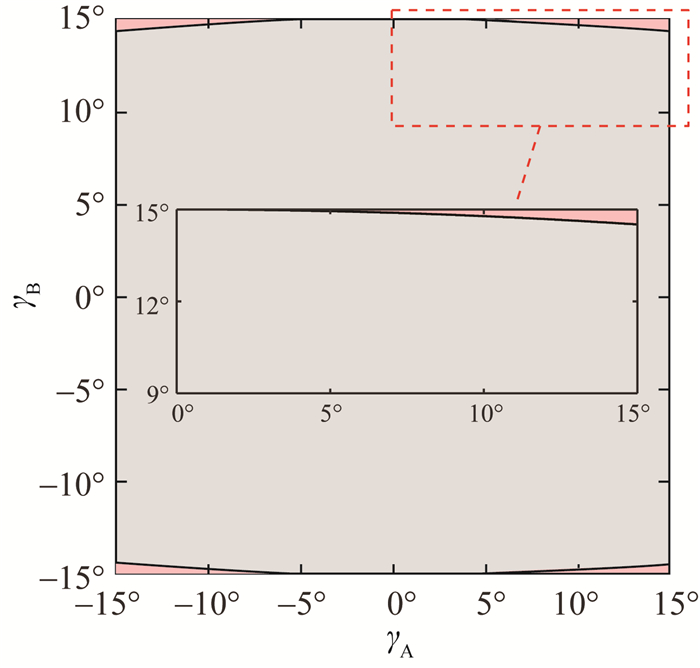

ξ=15°时对式(7)近似转化的误差见图 7,其中灰色区域为近似后的角度范围,浅红色区域为近似变化后γA和γB范围的缩减,两区域之和即为近似前γA和γB的范围。可见由该近似所导致的角度范围缩减很小,按浅红色部分的面积计算,仅占原角度范围(γA, γB∈[-ξ, ξ]) 的1.334%,因此该近似具有一定的合理性。

|

| 图 7 ξ=15°时约束近似转化前后γA和γB范围的变化 |

在对非凸不等式进行近似后,可以将力可行条件的判断转化为式(12)的凸二次规划问题的最优目标函数值与t7max2的大小比较问题。当且仅当优化问题有解且‖hXYZ*‖2≤t7max时,力可行条件成立。

| $ \begin{gather*} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}^{*}=\underset{\boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}}{\operatorname{argmin}}\left(\boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}^{\mathrm{T}} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}\right), \\ \text { s. t. } \boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{QP}} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z} \leqslant \boldsymbol{b}_{\mathrm{QP}} . \end{gather*} $ | (12) |

其中:

| $ \boldsymbol{A}_{\mathrm{QP}}=\left(\begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{R}_{0}^{\mathrm{T}} \\ \left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \\ -\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \end{array}\right), \boldsymbol{B}=\left(\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & -\tan \xi \\ -1 & 0 & -\tan \xi \\ 0 & 1 & -\tan \xi \\ 0 & -1 & -\tan \xi \\ 0 & 0 & -1 \end{array}\right), $ |

| $ \boldsymbol{b}_{\mathrm{QP}}=\left(\mathbf{0}_{1 \times 5}\left(-\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}-\boldsymbol{t}_{\min }\right)^{\mathrm{T}} \quad\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}+\boldsymbol{t}_{\max }\right)^{\mathrm{T}}\right)^{\mathrm{T}} . $ |

对该二次规划问题,考虑采用有效集方法求解,该方法较适用于中小规模问题,且可以很好地判断约束的可行性[24]。根据凸优化相关理论,该二次规划问题若有可行解,则必然能求得一个唯一的全局最优解[25]。因此,所求得的最优函数值必然为hXYZ在可行域上的最小模长,保证了‖hXYZ*‖2≤t7max与近似后的力可行条件成立相等价。

3.3 机器人力可行工作空间分析本节采用3.2节提出的计算方法对恒方向和变方向推进力下的力可行工作空间进行分析。表 1给出一组机器人的基本结构与力参数,作为计算和分析的依据。其中,t7max由文[26]中B型螺旋桨的数据估算得出。

| 参数 | 数值 |

| Rt/m | 5 |

| Rw/m | 3 |

| Rp/m | 0.5 |

| α1/rad | 5π/9 |

| α2/rad | 5π/9 |

| t7max/N | 600 |

| tmin/N | 50 |

| tmax/N | 300 |

1) 恒方向推进力。

先考虑恒方向推进力的情况,此时hXYZ完全由动平台的位姿决定。考虑推进力垂直于X′Y′平面,即hXYZ=R0hX′Y′Z′, hX′Y′Z′=(0 0 h3′)T.

该情况可以视作式(12)的优化问题在ξ=0时的特殊情况,也可以考虑去掉多余的不等式,将力可行条件的判断转化为仅关于h3′的线性不等式组求解问题:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{l} \boldsymbol{t}_{\min } \leqslant-\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}-\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \boldsymbol{r}_{03} h_{3^{\prime}} \leqslant \boldsymbol{t}_{\max } , \\ 0 \leqslant h_{3^{\prime}} \leqslant t_{7 \max }. \end{array}\right. $ | (13) |

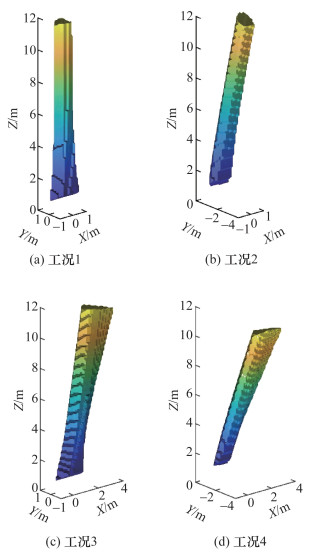

式(13)中,r03为R0的第3列。当A可逆时,采用该不等式只需进行有限步计算而无须迭代即可完成力可行条件判断。对机器人在动平台不同给定姿态、受到不同外界作用力下的4种工况(见表 2)的力可行工作空间进行求解,结果如图 8所示。

| 工况 | (θ, ϕ, ψ)/rad | wp/N |

| 1 | (0, 0, 0) | (0 0 0)T |

| 2 | (0.25, 0, 0) | (0 0 0)T |

| 3 | (0, 0, 0) | (100 0 0)T |

| 4 | (0.25, 0, 0) | (100 0 0)T |

|

| 图 8 恒方向推进力下机器人的力可行工作空间 |

由图 8可知,当推进力方向恒定时,机器人已经可以实现较远距离(10 m以上)的运动,然而当机器人的姿态一定时,其X和Y向工作空间范围很小,这说明机器人的运动能力仍受到较大限制。此外,力可行工作空间受动平台姿态和外界作用力的影响较大,图 8b和8c分别显示动平台绕X轴正向转动及受到X轴正向外力时,力可行工作空间将分别发生向Y轴负向和X轴正向的倾斜,而图 8d展示了动平台姿态和外力共同作用下,以上2种倾斜将同时发生。考虑到力可行工作空间的体积较小,这意味着机器人对姿态误差和外界干扰的抵抗能力较弱,容易发生失控现象。

2) 变方向推进力。

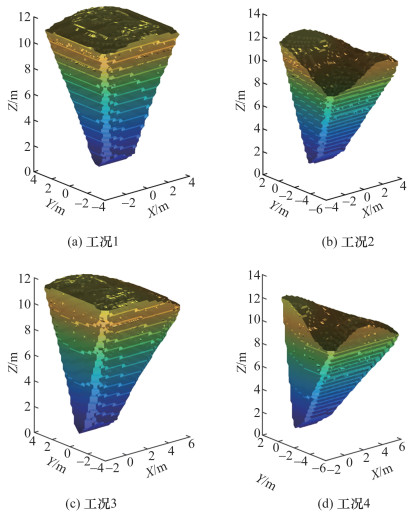

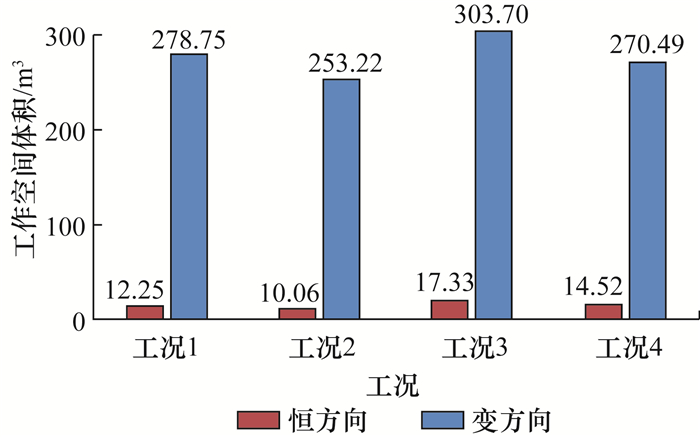

变方向推进力下动平台不同给定姿态、受到不同外界作用力时机器人的力可行工作空间如图 9所示。恒方向与变方向推进力下机器人4种工况的力可行工作空间体积如图 10所示。

|

| 图 9 变方向推进力下机器人的力可行工作空间 |

|

| 图 10 恒方向与变方向推进力下机器人4种工况的工作空间体积 |

由图 9可知,变方向推进力下机器人的力可行工作空间总体呈锥形,相比恒方向推进力下的情况,动平台的X和Y向运动范围增大,同时其Z向最远运动距离也可达12 m。当动平台发生倾斜或受到外界作用力时,力可行工作空间的倾斜趋势与恒方向推进力下相同,但通过推进力方向的变化,机器人能够在更大的空间和姿态范围内以及一定外力的作用下保持自身的平衡,失控的可能性大大降低。此外,通过图 10中对于力可行工作空间体积的对比,也可发现推进力方向的改变对于机器人工作空间体积的提升具有十分显著的作用。

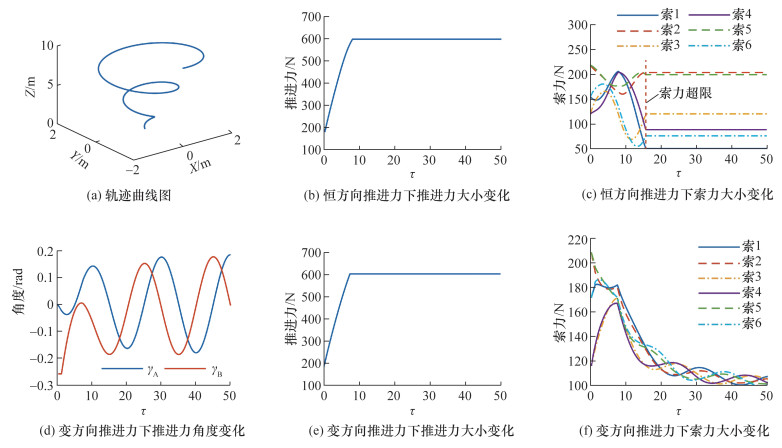

3.4 机器人轨迹运行仿真验证为了更加直观地说明变方向推进力方案能够有效提升动平台的运动范围,考虑选取一条较大跨度的轨迹,并考察恒方向和变方向推进力下机器人在轨迹上准静态运动时绳索索力和推进力的变化情况。

机器人的驱动数多于末端的自由度数,故对于大多数动平台位姿,可行的索力和推进力都不是唯一的。在这里采用优化方法确定每一种位姿下索力和推进力的解,本文参考文[27],采用式(14)的优化目标:

| $ \begin{gather*} \min \left\|\boldsymbol{t}-\boldsymbol{t}_{\mathrm{m}}\right\|_{2}= \\ \left\|-\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} \boldsymbol{w}_{\mathrm{p}}-\left(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\right)_{X Y Z} \boldsymbol{h}_{X Y Z}-\boldsymbol{t}_{\mathrm{m}}\right\|_{2} . \end{gather*} $ | (14) |

其中tm为可行索力空间的中心点,

选取一条螺旋线轨迹进行分析,如图 11a所示,轨迹的参数方程见式(15)。在恒方向和变方向推进力的情况下,机器人末端受力wp=0且准静态运行时的推进力和索力情况如图 11b—11f所示:

| $ \left\{\begin{array}{l} x=0.04 \tau \sin \frac{\pi \tau}{10}, \\ y=0.04 \tau \cos \frac{\pi \tau}{10}, \\ z=0.2 \tau , \\ \theta=\phi=\psi=0, \\ \tau \in[0, 50]. \end{array}\right. $ | (15) |

|

| 图 11 机器人轨迹运行仿真验证 |

由图 11c可以发现,在推进力方向恒定时,索力在τ=16左右时即已超出50 N的最小限制,此时机器人易出现虚牵问题;而图 11d—11f显示在变方向推进力下,通过对螺旋桨角度的调节可以明显减小机器人各索索力的波动,在τ∈[0, 50]的参数范围内,索力均保持在可行的范围内。这也说明变方向推进力的设计能够明显提升机器人的运动范围。

4 结论本文提出了一种变推进力的水下近端索驱动机器人。该机器人采用近端六索驱动,通过安装于两自由度变向机构的螺旋桨产生的推进力张紧绳索,此机构能够使机器人在各方向实现较大空间内的运动。建立了机器人的运动学与静力学模型,针对推进力方向可变的特点提出一种基于约束二次规划的力可行工作空间计算方法,并对恒方向、变方向下机器人的力可行工作空间进行计算与分析。结果表明,相比恒方向推进力下,变方向推进力下机器人的力可行工作空间体积得到显著增大。本文为此类机器人的进一步研究提供了一定的理论基础,后续可考虑根据机器人的动力学特性对机器人的控制方法展开研究。

| [1] |

李硕, 吴园涛, 李琛, 等. 水下机器人应用及展望[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2022, 37(07): 910-920. LI S, WU Y T, LI C, et al. Application and prospect of unmanned underwater vehicle[J]. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2022, 37(7): 910-920. (in Chinese) |

| [2] |

SIVČEV S, COLEMAN J, OMERDIĆ E, et al. Underwater manipulators: A review[J]. Ocean Engineering, 2018, 163: 431-450. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.06.018 |

| [3] |

TANG J Z, ZHANG Y G, HUANG F H, et al. Design and kinematic control of the cable-driven hyper-redundant manipulator for potential underwater applications[J]. Applied Sciences, 2019, 9(6): 1142. DOI:10.3390/app9061142 |

| [4] |

BAE J, BAK J, JIN S, et al. Optimal configuration and parametric design of an underwater vehicle manipulator system for a valve task[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2018, 123: 76-88. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2018.01.014 |

| [5] |

LIU T, HU Y L, XU H, et al. Investigation of the vectored thruster AUVs based on 3SPS-S parallel manipulator[J]. Applied Ocean Research, 2019, 85: 151-161. DOI:10.1016/j.apor.2019.01.025 |

| [6] |

BA X, LUO X H, SHI Z C, et al. A vectored water jet propulsion method for autonomous underwater vehicles[J]. Ocean Engineering, 2013, 74: 133-140. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2013.10.003 |

| [7] |

SIMONI R, RODRÍGUEZ P R, CIEŚLAK P, et al. Design and kinematic analysis of a 6-DOF foldable/deployable Delta parallel manipulator with spherical wrist for an I-AUV[C]// Proceedings of OCEANS 2019. Marseille, France: IEEE, 2019: 1-10.

|

| [8] |

PHILLIPS B T, BECKER K P, KURUMAYA S, et al. A dexterous, glove-based teleoperable low-power soft robotic arm for delicate deep-sea biological exploration[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 14779. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-33138-y |

| [9] |

PHAM C B, YEO S H, YANG G L, et al. Force-closure workspace analysis of cable-driven parallel mechanisms[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2006, 41(1): 53-69. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2005.04.003 |

| [10] |

ALBUS J, BOSTELMAN R, DAGALAKIS N. The NIST robocrane[J]. Journal of Robotic Systems, 1993, 10(5): 709-724. DOI:10.1002/rob.4620100509 |

| [11] |

YAO R, TANG X Q, WANG J S, et al. Dimensional optimization design of the four-cable-driven parallel manipulator in FAST[J]. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 2010, 15(6): 932-941. |

| [12] |

MAO Y, JIN X, DUTTA G G, et al. Human movement training with a cable driven arm exoskeleton (CAREX)[J]. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 2015, 23(1): 84-92. DOI:10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2329018 |

| [13] |

ZAREBIDOKI M, DHUPIA J, XU W L. Dynamics modelling and robust passivity-based control of cable-suspended parallel robots in fluidic environment[C]// Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mechatronics and Robotics Engineering. Budapest, Hungary: IEEE, 2021: 48-53.

|

| [14] |

EL-GHAZALY G, GOUTTEFARDE M, CREUZE V. Hybrid cable-thruster actuated underwater vehicle- manipulator systems: A study on force capabilities[C]// Proceedings of 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Hamburg, Germany: IEEE, 2015: 1672-1678.

|

| [15] |

HOROUB M M, HASSAN M, HAWWA M A. Workspace analysis of a Gough-Stewart type cable marine platform subjected to harmonic water waves[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2018, 120: 314-325. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2017.09.001 |

| [16] |

GOUTTEFARDE M, RODRIGUEZ M, BARRELET C, et al. The robotic seabed cleaning platform: An underwater cable-driven parallel robot for marine litter removal[C]// Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cable-Driven Parallel Robots. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2023: 430-441.

|

| [17] |

ZI B, WANG N, QIAN S, et al. Design, stiffness analysis and experimental study of a cable-driven parallel 3D printer[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2019, 132: 207-222. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2018.11.003 |

| [18] |

ZHANG Z K, SHAO Z F, WANG L P, et al. Optimal design of a high-speed pick-and-place cable-driven parallel robot[C]// Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Cable-Driven Parallel Robots. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2018: 340-352.

|

| [19] |

LEE K, KO K, PARK S, et al. Obstacle-overcoming and stabilization mechanism of a rope-riding mobile robot on a façade[J]. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 2022, 7(2): 1372-1378. DOI:10.1109/LRA.2021.3139953 |

| [20] |

SEO K, CHO S, KIM T, et al. Design and stability analysis of a novel wall-climbing robotic platform (ROPE RIDE)[J]. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 2013, 70: 189-208. DOI:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2013.07.012 |

| [21] |

HAYASHI K, SUGAHARA Y, TAKEDA Y. Experimental study on thrustered cable-suspended parallel robot for collaborative task[C]// Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Cable-Driven Parallel Robots. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2023: 419-429.

|

| [22] |

刘超. 绳索驱动六自由度运动系统尺度综合与控制研究[D]. 哈尔滨: 哈尔滨工业大学, 2019. LIU C. Study on dimensional synthesis and control of 6-DoF cable-driven motion system[D]. Harbin: Harbin Institute of Technology, 2019. (in Chinese) |

| [23] |

GOUTTEFARDE M, DANEY D, MERLET J P. Interval-analysis-based determination of the wrench-feasible workspace of parallel cable-driven robots[J]. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2011, 27(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1109/TRO.2010.2090064 |

| [24] |

陈文标. 线性约束的凸二次规划求解算法研究[D]. 武汉: 武汉大学, 2022. CHEN W B. Research the algorithms solving convex quadratic programming with linear constraints[D]. Wuhan: Wuhan University, 2022. (in Chinese) |

| [25] |

BOYD S, VANDENBERGHE L. Convex optimization[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

|

| [26] |

BARNITSAS M M, RAY D, KINLEY P. Kt, Kq and efficiency curves for the wageningen B-series propellers[R]. Ann Arbor, USA: The University of Michigan, 1981.

|

| [27] |

POTT A. An improved force distribution algorithm for over-constrained cable-driven parallel robots[C]// Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Computational Kinematics. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 2014: 139-146.

|